Author: Lucía Anabitarte, communicator at COPOLAD III

It has been a long flight and the humid heat of Cali hits us and keeps us warm in equal parts. We have left behind us an early autumn in Madrid where the first rains are coming, but where the countryside is still yellowing. We arrive at night and for me it is a new city (and a new country), so I amuse myself by looking out the window of the car that takes us to our accommodation, trying to catch a glimpse of the colours and shapes of the city in movement.

Cali is Colombia’s third largest city and the epicentre of salsa. Our destination on this trip is commune 9 and, in particular, the neighbourhood of Sucre, one of the most vulnerable communities in the country.

For the last year, the Agirre Lehendakaria Center of the University of the Basque Country, within the framework of COPOLAD III, has been developing several social innovation laboratories in Sucre (Cali) and El Porvenir (Santander de Quilichao). It does so together with the Colombian Ministry of Justice and Law, associations related to problematic drug use, security forces, health, education and youth, among others. They are called ‘laboratories’ because they are spaces for experimentation, ‘innovation’ because they seek to provide different answers through shared learning, and ‘social’ because they do so with proposals that come from the communities themselves.

It is a formula that soon fascinates me, as it allows experimentation and testing of solutions to the challenges presented by a specific reality and from the initiatives of those who live there. These laboratories promote possible realities that distance these communities and their inhabitants from the stigma and narratives that block changes in the self-perception of drug users and social advances in the neighbourhood. In the context of Cali and Santander de Quilichao, these laboratories seek to address social inclusion and the drug problem with a focus on young people in vulnerable situations.

Thanks to a process of listening to civil society and local institutions and mapping existing initiatives that address this issue, more than 40 proposals have been put forward so far. These include an urban vegetable garden, a community restaurant, a cultural house, a cooperative of gastronomic enterprises led by women and a food museum. All with a key objective: to prevent drug use and avoid the involvement of young people in illegal economies.

The laboratories are one of the lines of work promoted by COPOLAD III within the framework of Colombia’s National Drug Policy, which has as one of its central axes the change of narratives, the reduction of harm associated with drug use and social inclusion. In the face of extreme vulnerabilities, these spaces for co-creation foster positive narratives and a strong resilience that drives local action in the face of stigma. “The laboratories have identified all the existing resources in the territory and have set in motion a listening process to understand in depth all the dimensions of this problem. In addition to public institutions, the initiative has given a voice to the community and young people in vulnerable situations”, says Julia Martínez, from the Agirre Center team.

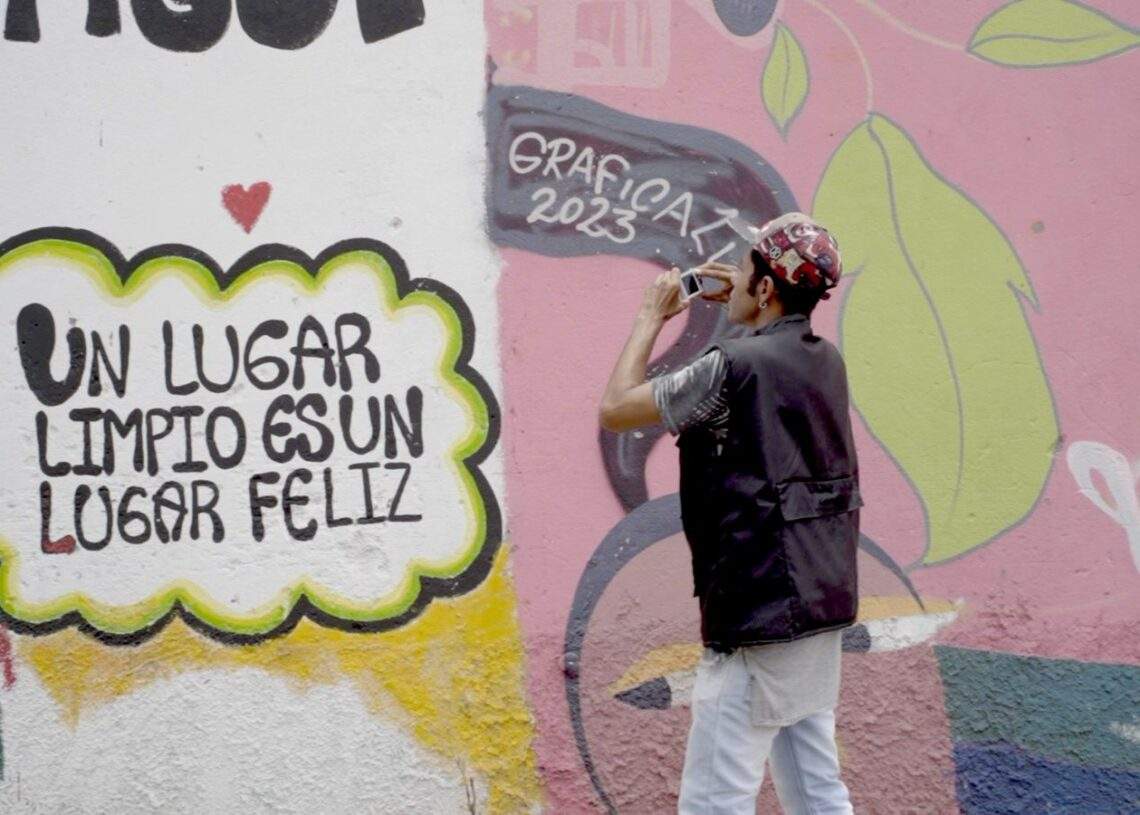

Our visit to Cali concludes with the closing of the ‘Forest of Memory’ workshop, an initiative of the Colombian Ministry of Justice and Law to build and transform narratives in communities affected by drugs and drug trafficking. I believe that art is a powerful tool for listening, communication and change, and I see how this space allows the transformation of the territory from the voice of its population to promote territorial public policies accordingly. A different kind of listening space that encourages, through images, the inhabitants of the neighbourhood to promote possible realities, break with stigma and build new landscapes and collective imaginaries of their community.

The workshop, developed by the VIST (‘Visual Is Telling’) Foundation, ends with a series of photographs taken by the participants in the neighbourhood to express the problem from their daily lives, offer solutions to it and continue weaving community ties.

Jorge Moreno Blanco, a VIST workshop leader, tells me how the workshop went: “they arrived saying they were addicts”. Sometimes, in this society, “someone who has a consumption problem cease to be someone and becomes their consumption. Over time I feel that they themselves, seeing themselves as part of these processes, see that there are people who look at them from another side and they themselves feel that they can be other things. One of the participants told me ‘teacher, it’s been a long time since anyone looked at me with dignity like you do, and that’s very valuable for me’”.

“Cease to be someone and become their consumption “

I am struck by these words and reflect on the importance of restoring dignity to drug users. I believe that words have the power to embrace, but also to wound and scar the skin. I think it is a social responsibility to heal these scars and to work on changing the language and the way we look at people who use drugs and the communities they live in so as not to reproduce the stigma to which they have been subjected for so long. This is why I feel that the work of COPOLAD and public policies is so important to continue contributing to changing this channel.

One of the young people involved is Jefferson. He is 32 years old, is on methadone treatment and comes to Corporación Viviendo to take part in different activities offered: a course to learn how to make air fresheners or how to make bracelets from Chinese thread. He shares his life story with us and thanks us for being there. However, I am the one who feels that I cannot thank her for the enormous generosity of sharing so much intimacy.

At this moment I cannot help but have a thought that is key for me: I am passing through here, I touch this reality fleetingly. Hence the importance of a public policy that generates sustainability over time, makes a long-term commitment to a need and employs economic and human resources to address it. Only through this institutional commitment and with the knowledge of civil society can we build lasting public policies that are connected to reality and that displace the narratives that stigmatise people with problematic drug use. I feel fortunate to be able to be part of this process and to communicate these social changes so that words leave no trace on the skin.